Ideas Platform

Michelle Ussher

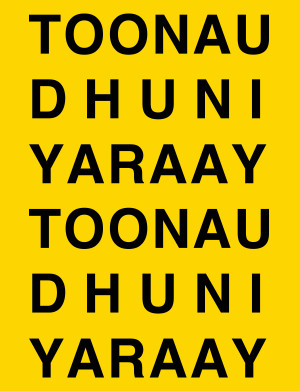

The Mind goes out to Meet itself

16 May – 31 May 2015

Artspace

43–51 Cowper Wharf Roadway

Woolloomooloo NSW 2011

Sydney Australia

Featuring a sound collaboration with composer Huw Hallam and soprano Frederica Cunningham. Crochet by Judith Ussher

Aphrodite—‘foam-born.’ She was the ancient Greek goddess of desire, fertility and procreation, love and beauty. Some say she was born when Cronus cut off the genitals of Uranus and threw them into the sea nearby the island of Cythera where they gestated, the goddess consequently emerging from the foam. When Aphrodite first stepped ashore, her very footsteps blossomed, leaving a trail of flowers and grass in her wake. Still today, seafood is regarded as an aphrodisiac throughout the Mediterranean region. Foam-born, Hesiod interpreted Aphrodite as having risen from Chaos, dancing on the sea. Other ancient Greek myths, such as that of the heavenly Sirens, who lured sailors to their death-by-shipwreck and feature in Homer’s Odyssey, establish a more destructive affiliation between the feminine and the watery body.

The Mind goes out to Meet itself forms part of a body of work developed by Michelle Ussher while in residence at Artspace and exhibited in Is it your body I hold in my arms or the sea? at Station Gallery, Melbourne. The images, myths and archetypes that subtend the works concern the symbolic relationship between woman and water. Woman qua water—as chaos, as uncontained, shapeless and shape-shifting, leaking. As having the capacity to make something or someone float, or drown. (This liquidity inheres in the medium of paint itself, which is, of course, fluid when applied to a surface.)

Surrounding the wall works and ceramic sculptures is a score by composer and collaborator Huw Hallam, which is a combination of field recordings—waves, water lapping at a port, the sound of urine hitting a porcelain bowl, a tap dripping—and operatic vocals by the female soprano, Frederica Cunningham. Hallam’s composition is based on the libretto written by Ussher, which was, in turn, based on six passages from British writer Ann Quin’s 1969 novel Passages, to which the artist ‘responded.’ At one point, Cunningham trills:

Go around what you cannot go through

Remain formless, flow,

Choose who

Floats who

Drowns

The score becomes the invisible support mechanism in which the exhibition’s physical objects are nested; it is the artist’s effort to ‘hold’ the show together—to contain it. Naturally, though, the sounds of Hallam’s composition are edgeless and cannot be contained—they spill throughout the space, the sonic frequencies rush into the bodies of viewers, at times overwhelming them, at other times seeming to lie dormant, barely perceptible.

Many of the images that surface in the paintings of this exhibition stem from a research trip that Ussher made to Greece in 2013, and therefore refer directly to the familiar postures, myths and figures of classical antiquity. In Greece, she viewed an exhibition of objects salvaged from a first-century BCE shipwreck off the coast of the Greek island of Antikythera. In 1900, divers discovered numerous coins and statues dating back to the fourth century BCE on the ocean floor, many of which had formed curious and seemingly decorative patinas from decay, due to their long-term submersion in salt water.

Also in 2013, Jonathan Glazer released his film Under the Skin to the applause of many critics who lauded it as a strong feminist science-fiction story, and to the annoyance of Ussher, who viewed it as yet another rehashing of misogynistic stereotypes on screen. Glazer’s film traces the story of a sexless alien beamed down to earth who then promptly adopts the highly sexualised body of one Scarlett Johansson. For whatever unknown reason, the alien hunts down men off the street whilst driving a large white van, she seduces them, and then kills them through their sex act by a miraculous, supernatural form of drowning followed by rapid evisceration. Ussher related the film to the medieval English myth of Viviane, the Lady of the Lake, who seduced the sorcerer Merlin in order to purloin his spells. Once she had extracted them, Viviane dispensed with Merlin—trapping him in a cave, under a rock, or in the stump of a tree, depending on which story you read. Merlin’s head is represented in one of the hollow, white and blue–painted porcelain vessels. Light and sound drift through the perforated bust, no longer a whole.

Combined with the images and myths of antiquity in Ussher’s work are more contemporary images made possible only by Photoshop. In processing her irritation with Under the Skin, Ussher Googled ‘Scarlet Johansson porn’, looking for images in which Johansson’s face had been stitched onto pornographic actresses’ bodies. The willingness of people to cut up the digital body of Johansson (to behead her) and splice it with other, less renowned actresses reflects the violence enacted on her character in the second half of Under the Skin, where whatever was supposedly triumphantly feminist about the first half of the film is utterly and traumatically inverted. In the second half of the film (N.B., spoiler imminent), Johansson abandons her alien connection in search of a human, female identity, only to become—in a reversal of the first half of the film—an all- too-familiar female victim, who is, in turn, hunted down, becomes the victim of an attempted rape, before being burnt alive.

Painting, sound and ceramic—a series of pools. Sites and surfaces for receiving and projecting images and objects and narratives, which float, sink and rotate. Infinitely shallow and infinitely deep.

Helen Hughes