Artist

Club Ate

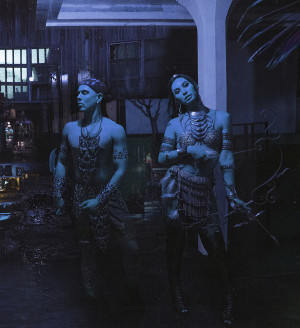

Club Ate is a collective formed in 2014 by multi-form artists Justin Shoulder and Bhenji Ra. Their practice traverses video, performance and club events with an emphasis on community activation. Collaborating with members of the queer Asia Pacific diaspora in Australia and the Philippines, the collective are invested in creating their own Future Folklore. Past Club Ate events have taken the form of Pageants, Variety Nights and Balls.

The collective have performed and exhibited internationally, with recent highlights including The 8th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, QAGGOMA, Brisbane, 2015-16; Fault-lines: Disparate and Desperate Intimacies, ICA Singapore, 2016; AsiaTOPA, ACMI, Melbourne, 2017; and Balik Bayan, Blacktown Arts Centre, 2017. They were also a finalist in the Singapore Art Prize at the National Museum of Singapore and have recently completed an Asialink Residency hosted by Green Papaya Arts, Philippines, 2018. They are currently working on the next episode of their video project Ex Nilalang; Queen of Horror to premiere in 2020.

In Conversation

Club Ate (Bhenji Ra and Justin Shoulder) in conversation with Artspace Executive Director Alexie Glass-Kantor

Alexie Glass-Kantor (AGK): [Can you] tell us a little bit about how you both began individually as artists and how you’ve come together?

Justin Shoulder (JS): I went to [what is] now known as UNSW Art & Design, COFA, but I feel like my interest in performance and art has always been there, not necessarily starting with training but one of the most iconic images in my childhood is watching the Chinese dragon parade in primary school and just feeling this intense sense of fear and wonder. I always think back to that moment thinking that's probably where my interest in masks and community transformative spectacle began. And ever since then me and my sister were making costumes and doing little shows at home. I kind of moved away from performance and I studied digital media at COFA, mostly focused on photography, sound, image-making and I went into doing a full-time job as a retoucher and I thought that was going to be my vocation. But at the same time, gosh that was like 12, 13 years ago, I met my partner, Matt Stegh, and really I say my education started in the night club. At that time there was a lot more cabaret stuff happening in Sydney and it was kind of the end of Lan Franchis and there was a lot more stuff happening at 34B. It was the mid time of Club Kooky and I got introduced to a huge family of artists. I was living with Dallas de la Force - I was leaf blowing her wigs on the weekends as part of her shows - and I think I then got introduced to this whole community of mostly cabaret, stripping, clowny kind of artists and I still work with these same artists today. Soon after we formed a collective called the Glitter Militia that came from entering in the Mardi Gras parade and there was a group of us - a mixture of activists and artists and sex workers - and with a kind of, not really like a uniform unified politic, but a real mess of voices. What drew us together was probably the mess and the kind of anarchy of it all. Then I started performing and doing performance nights with Matt Stegh and a group of other artists and Monsta Gras kind of took form with Lady P, Penelope Benton.

So we’ve been doing that for – this was our ninth year this year – and concurrently doing performance but often creating spaces and facilitating voices, and that's very similar to what me and Bhenji do as well. I’ve been building on this body of work called Phasmahammer. Mostly I guess it’s invented mythologies and more recently seen as a future folklore that's grounded in my ancestral lineage in the Philippines. In the beginning it was much more like a sculptural reconstruction of my form and then I started to think more about what these myths were and where they come from and how I can really ground it in my own foundational narratives. We met like 6 years ago, like a lot of people and collaborators, in the club in Perth and we just kind of had this lightbulb moment where we both discovered we had this connection through nightlife but also through our mother tongue. We started to think about how we could have this exchange because we have…although there’s la lot of similarities, our practices have quite different forms so I think we were really excited about what that meant.

Bhenji Rah (BR): I always had an interest in, I think, the visual arts…Excuse the pun, but I’ve always danced between the visual arts and the dance world growing up. I grew up in Moruya, so the South Coast. I think having a migrant mother and also being kind of very visibly queer from a young age I was very, very different from everyone else, so like everyone else that is a bit of a weirdo in high school I just kind of gravitated…towards the art teacher and she was also the multicultural officer as well. So whenever I had problems or issues with race I would always go to her and then she would always encourage me, so I think this kind of relationship between the social-political and art, as being this device to kind of negotiate that, started from a really young age. Then actually my HSC work was in Art Express at the Art Gallery of NSW.

AGK: Oh you made it in!

BR: I made it!

AGK: Amazing!

BR: It was funny because I was actually asked to give a lecture and it was me and David Griggs doing the lecture at the time. I don’t think he would remember me at all, but I already had questions for him to do with his work because my work itself was about my time in the Philippines when I was visiting a women’s prison. I was like 16, 17 and I was doing dance workshops with the women in prison because my aunty had an outreach program there for them. Then I started a mailing group between the women who were incarcerated and students of the high school and then this became a documented form kind of thing. So that was really like ‘oh yes, this is what I want to do. I want to become a social political artist’ and this felt really affirming to my identity. But then I came across contemporary dance and I was like, ‘actually, this is so much more abstract!’. And I was young, it was actually after the David Griggs thing and I was like ‘I don’t know if I want to go to art school’ and this lady came up to me and said ‘you don’t need to go, you’ve got it already! Maybe just go to dance school or something.’ Then I ended up going to New York and studying at the Martha Graham School and after the Martha Graham School I went to the Western Academy, WAAPA.

AGK: So that’s why you were in Perth?

BR: That’s why I went to Perth for three years and that’s where I met Justin.

JS: We just met at a club night.

BR: We met at a club night in Perth in my last year. But I guess having gone through that fire of what it means to become this blank canvas for the dance world and having this kind of virtuosic practice really grounded me physically and just made me embody the politics that I wanted to express at an early age. Instead of creating sculptural things or documented forms, I was like ‘I want to embody this’ because my body is also political as it is. So now I’m kind of going in between, but meeting Justin was kind of this lightbulb moment, that these two practices that were maybe on the same journey together and have now found each other - him really wanting to break out even more into performance and body work and me having already done that but greatly missing some real hardcore visual art craftmanship around it and also wanting to engage in deeper theory around club practice and art world hierarchies and power dynamics and political issues as well. It felt so perfect and the fact that we could have the thread between us that we both have a matrilineal line of Filipino was kind of perfect.

AGK: And with Club Ate, did you move over for the collaboration? Did you move to Sydney so you could work together?

BR: We met in my final year at WAAPA and I was already coming to Sydney and we started to perform together a little bit. Justin invited me to be part of the Glitter Militia’s event at MCA Art Bar. We performed in it and there was this moment that he was O O and I was some sort of avatar or something like that, but it was really [about the] body and this crafted mask performing together, and we like ‘yes, we need to perform together all the time!’ Then we had the commission from Art Bank, Deep Alamat, and that was like ‘ok, what is this really about, where do we want to go with our interest in Filipino mythology?’ ‘Alamat’ means legend and let’s think deeper about what these legends mean on a social, cultural, daily level as well. I think at the time it was 2015 and typhoon Yolanda had hit in the Philippines and that had wiped out almost the entire city of Tacloban and almost 2,000 people were killed when that happened. I was over there at the time and ended up going down there to do some work on outreach for them and I met a lot of girls there and we connected. Coming back to Sydney we decided to would have a performance night called Club Ate and that would be a fundraiser for the community over there, specifically for the queer community as well, and we were like ok, Club Ate is a really cute name.

JS: The first one was a variety night.

BR: It was a really random variety night and we really had to kind of…searching out who was queer and of the Asian diaspora was actually really difficult. We were like ‘who is around?’. It was hard to put together people on the first [one] because there weren’t any artists out there who were part of that community at the time. And it’s funny because the community is so strong. You can name queer people of colour and there is such a huge community now and it is so strong, but at the time it was hard work to get people together and it just felt right that we had our aunties there cooking food and children there. It just made sense on an intergenerational level.

JS: Yeah totally.

BR: But that really formed a lot of…

JS: It just kind of flowed from that. Because ‘ate’ means ‘bigger sister’, we’ve just let it be quite organic and sometimes we get more institutional invitations, like when we did APT. That was the beginning of the work Ex Nililang which was the Art Form series. But we are really interested in what it means to sit between the kind of community space, doing the balls at the Addison Road Centre, and then doing something at a big institution. And that has been exciting. It kind of exists in so many different spaces and in components as well as like a body of work.

AGK: It is a bit like a lung isn’t it. Sometimes it breathes in and it can take in more, then you exhale and it kind of shifts again. It’s kind of interesting, moving in and out of different communities and spaces and expanses and ways of bringing together image and body.

JS: Yeah for sure, definitely. It’s exciting now. One of our collaborators, Corin, who we’ve been working with for the last three years it’s like we’ve started to create our own…there are really strong motifs and iconography for the collective and the sound and image world.

AGK: How would you describe those?

JS: Definitely future folklore. It will draw from something very ancient but it’s very forward, future looking. That’s what I think it is.